Amiko hydras

Kirby-Paris and Buchholz hydras

Hydras are a classic iterative game played on trees, known by googologists for the fast-growing functions derived from them and by serious mathematicians for their contributions to ordinal analysis. Unlike their combinatorial counterparts like TREE and SCG, no search is required to compute these fast-growing function values - just keep applying the transformation rule to the tree until the game says to stop.

Kirby-Paris hydras came first. For Kirby-Paris hydras, the rules are simple. Start with your hydra, which is an unordered unlabelled rooted tree. At each stage, choose a leaf node \(C\) to chop and a non-negative integer \(N\). If \(C\) is a child of the root, it is removed from the tree and that’s it. Otherwise, let \(P\) be \(C\)’s parent, and \(G\) be \(P\)’s parent. Remove \(C\) from \(P\), then add \(N\) copies of the modified \(P\) as children to \(G\). The game ends when the hydra is reduced to a single node.

To obtain a fast-growing function, we can fix \(N\), say, \(N = 1\) at the first step, then \(N = 2\), \(N = 3\), and so on, and decide on a simple rule for where to cut, say, always choosing the rightmost leaf. Then, \(Hydra(k)\) is the number of steps needed for the game to end starting with a path of length \(k\), that is, a linear stack of \(k + 1\) nodes.

Buchholz hydras extend Kirby-Paris hydras with labels, and require a few extra transformation cases. \(0\)-labelled nodes behave the same as in the Kirby-Paris hydra game. Integers greater than \(0\) turn into their predecessor but make the tree deeper. \(ω\), rather than being chopped, turns into the current value of the step counter, more or less. I won’t explain Buchholz hydras in detail here, but you can read more about them yourself.

Googology wiki has fine articles on Kirby-Paris hydras and Buchholz hydras, which I suggest you read before coming back here.

In this post, I introduce a higher extension of these hydras, which I believe is interesting in its own right.

An idea to nest hydras

In exploring ways to build faster growing functions than the one based on Buchholz hydras, a natural question to ask is “what if we used higher ordinals as labels?” and then since hydras are ordinal-like, “what if we used nested hydras as labels?” We can skip the details of adapting ordinal transformation rules for hydras right now, but in any case, these nested hydras are surely more powerful than plain Buchholz hydras.

I then thought to add a singleton, which I’ll call \( \lambda \). When encountered, it would expand into a hydra involving labels which are hydras involving labels which are hydras… \(N\) layers deep, containing no mention of \( \lambda \). This is, in some sense, a fixed point ordinal of hydra nesting, or for accuracy, the first common fixed point of whatever ordinal operation nesting hydras corresponds to. I cannot think of what ordinal such a system corresponds to, but surely it is stronger than without \( \lambda \). Why stop there? We can rename \( \lambda \) to \( \lambda_0 \), then introduce \( \lambda_1 \), the second common fixed point of hydra nesting, which expands like \( \lambda_0 \), except the nested hydras contain \( \lambda_0 \). Why stop there? We can make subscripts ordinals, or even hydras. Then we can add another layer, say, \( \xi_0 \), the first common fixed point of \( \lambda \) nesting, which expands into a stack of nested \( \lambda \) hydras, and so on.

Visualizing nested hydras

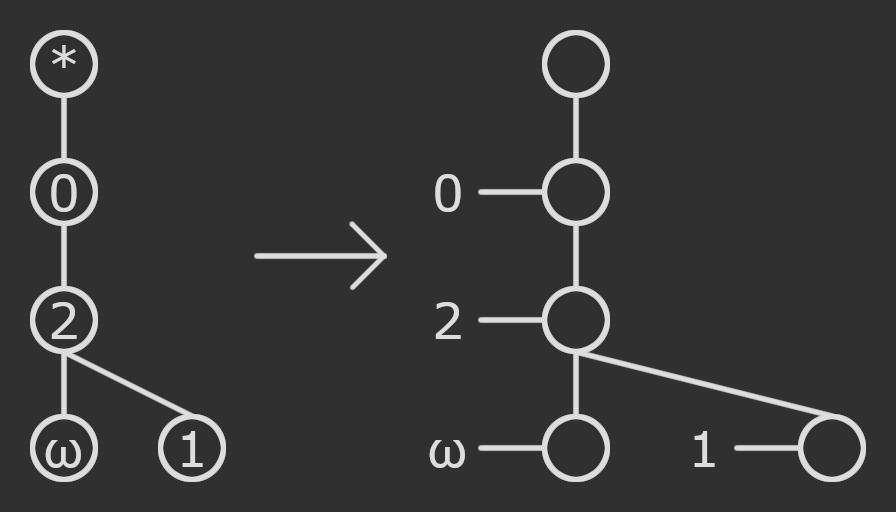

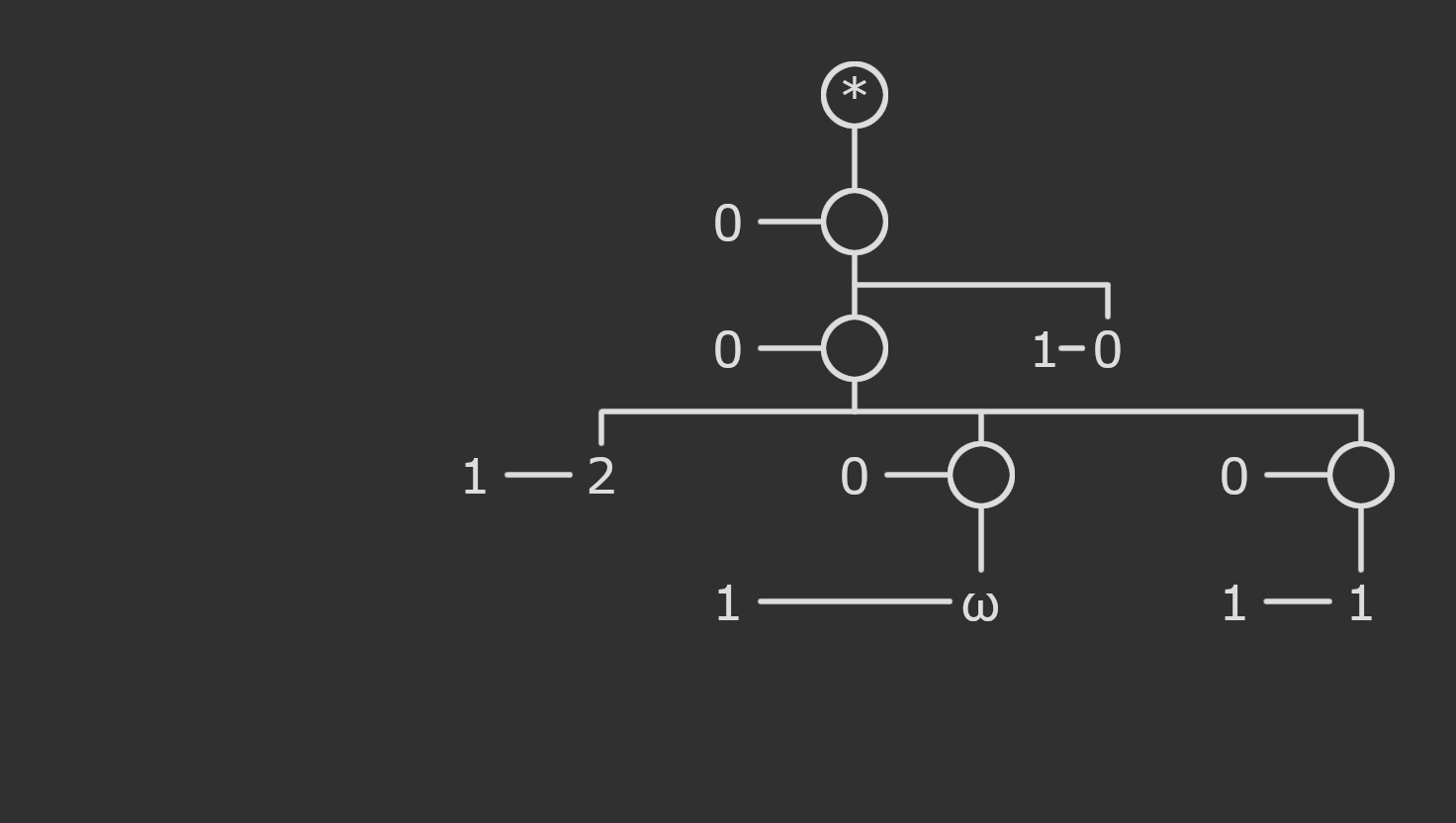

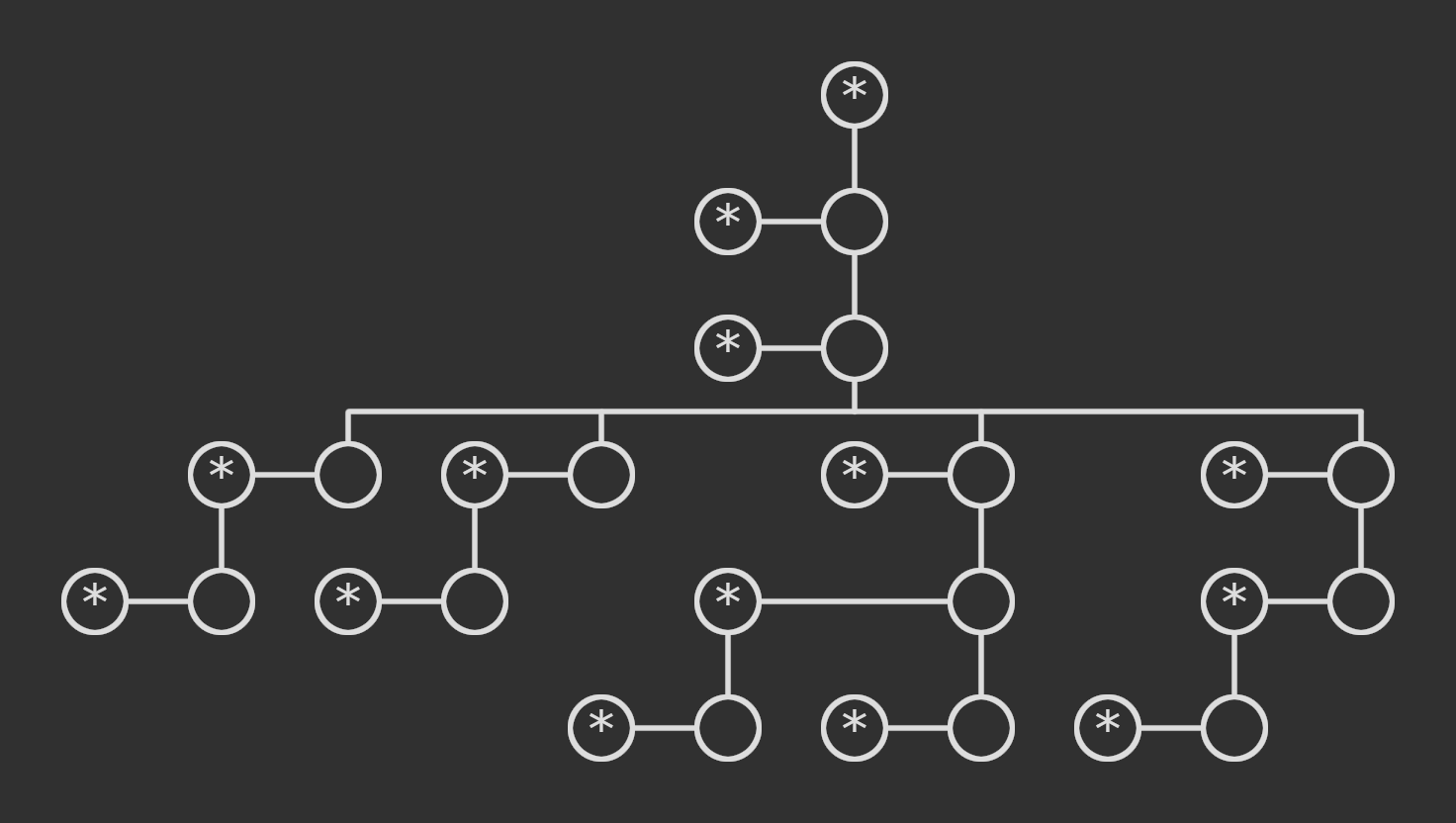

Before we proceed to make stronger hydras, I should show a method to draw nested hydras. It would be inconvenient to try and embed a diagram of a hydra within a single node, and possibly even do that recursively. Instead, I propose drawing the label to the left of the node, connected using a sideways edge.

This looks unnecessary and silly when the labels are small ordinals like this, but when we use hydras as labels, this becomes much more practical.

Externalize and close

“Externalize” and “close” are some important basic transformation types in our toolkit of higher order transformations on hydra constructions. “Externalize” means to shift information from the labels (internal) toward the children (external), with the end goal of putting an upper bound on the labels without changing the strength of the construction. “Close” means to take a construction where labels are upper-bounded, and extend it to support arbitrary hydras as labels, thus taking the closure of the construction under using hydras as labels, and making the construction stronger. These form a natural pair. I call these transformation types because there is not just one way to externalize or close, and different possible transformations may differ in strength.

Amiko hydras can be derived from Buchholz hydras with a close step, a somewhat strong externalize step, then a close step. The interesting step here is the externalize. I’ll walk you through converting the example hydra from above, and then discuss the strength of the system.

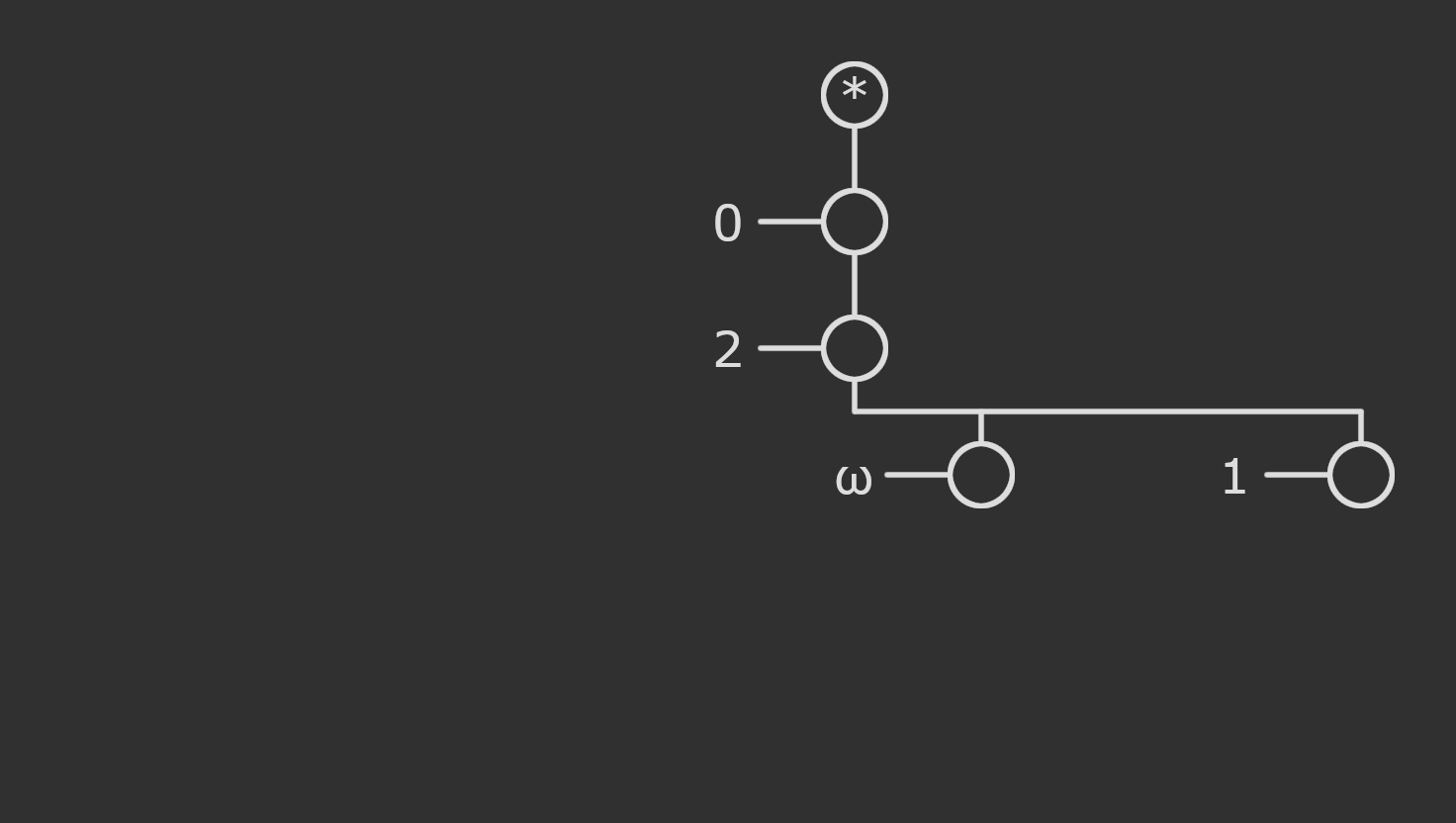

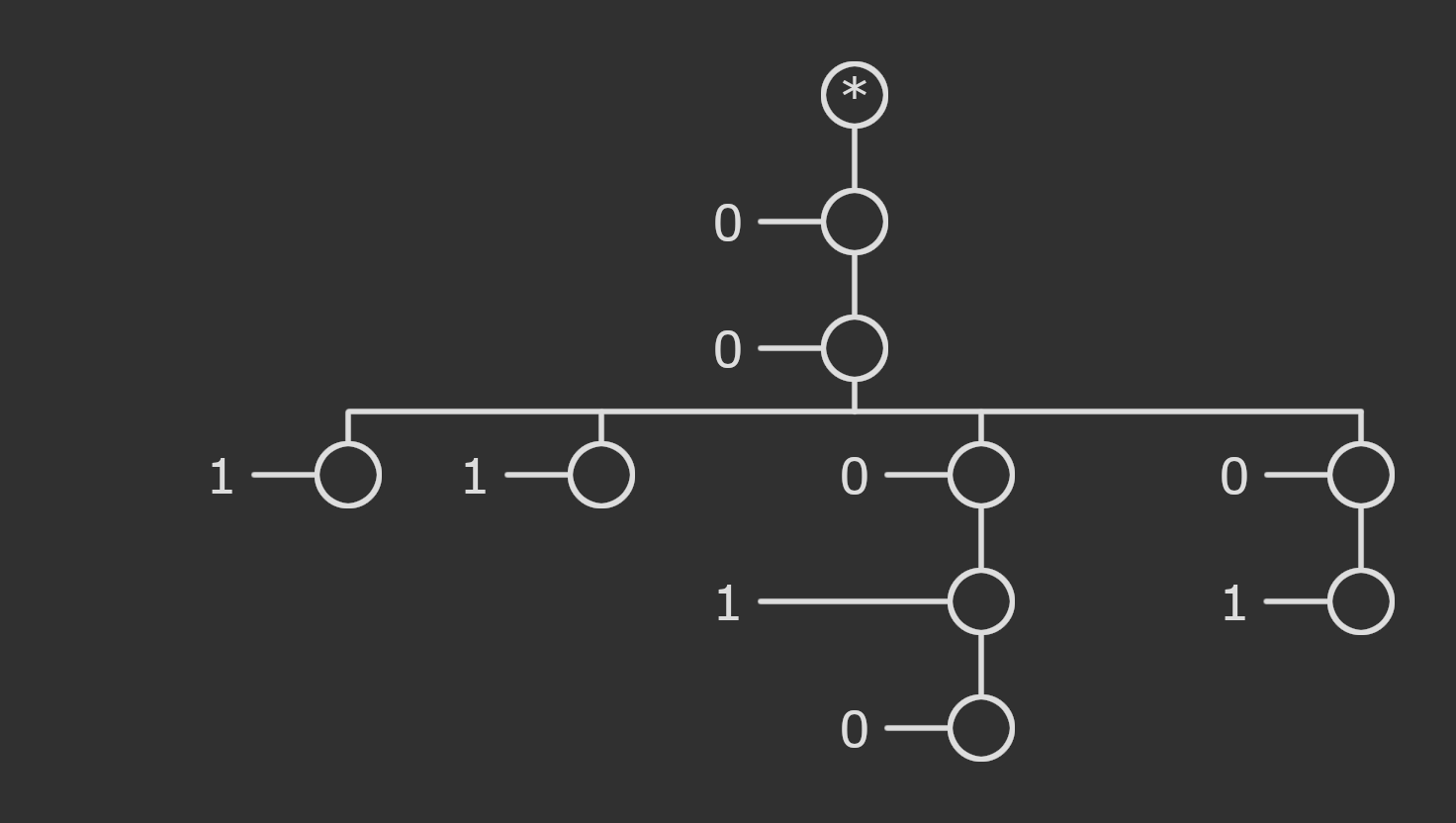

We’re first going to mark all existing edges with label \(0\).

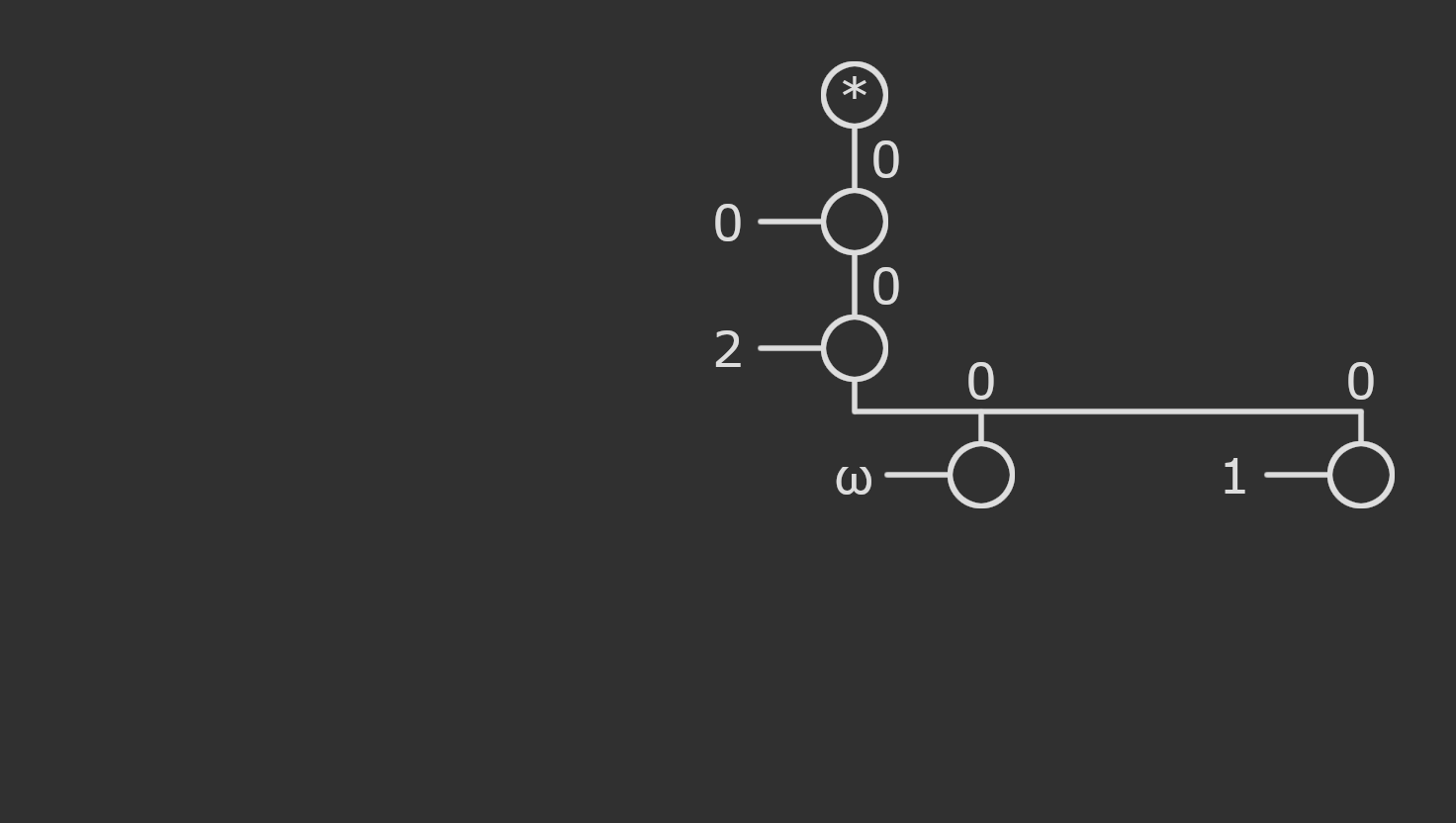

We’re then going to move the current label into a child node, with edge labelled \(1\).

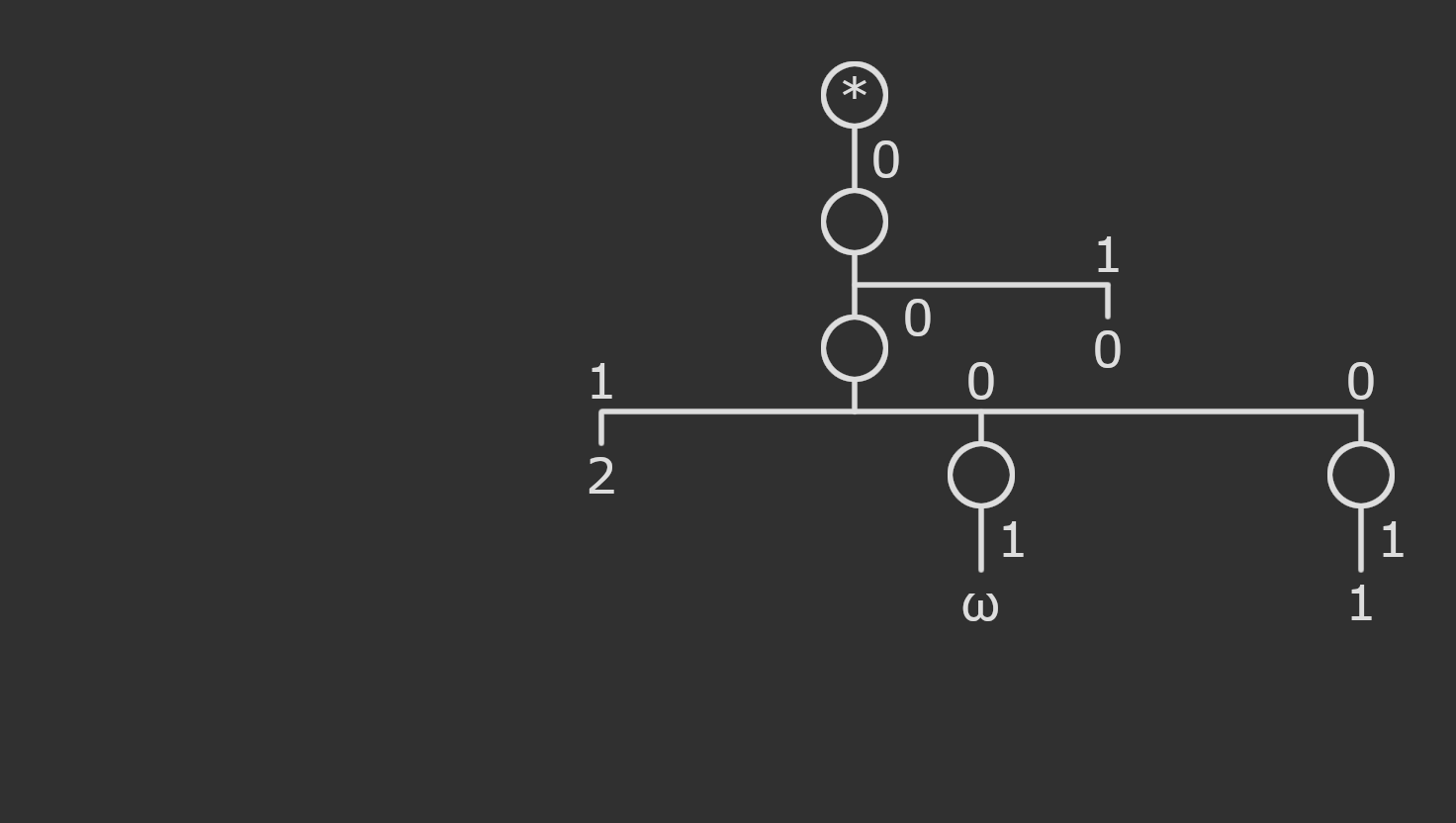

All original labels have now been evicted. We transfer these edge labels into the now unlabelled children. The root could be considered to have a special fake label, or no label.

We then expand these former labels into the corresponding hydras but with immediate children of the root changed to have label \(1\), and then merge the root of that hydra into the node from which the label originated. Recall that the lone root hydra is ordinal \(0\), a hydra with \(n\) children is the ordinal \(n\), and the hydra \(((()))\) is the ordinal \(\omega\). You’ll notice in this step since \(0\) turned into \(()\) and got fused with its parent, that branch just disappears, and since \(2\) turned into \((()())\) and got fused with its parent, it gained another child with label \(1\).

We’re almost there! We just need to get rid of the remaining ordinal labels by recursively converting them into hydras.

There we have it, our first Amiko hydra! Whatever rules we use to define its evolution, it should evolve pretty much the same as Buchholz hydras, for hydras that were converted from Buchholz hydras.

Amiko hydras with only \(0 = (\star:)\) and \(1 = (\star:((\star:):))\) labels correspond to nested Buchholz hydras. Amiko hydras with labels below \(\omega = (\star:(0:(0:))) = (\star:((\star:):((\star:):)))\) correspond to hyper-nested Buchholz hydras with a finite number of hyper-nesting dimensions, which we may collectively call \(\textrm{hyper}^\omega\)-nested Buchholz hydras. The full construction of Amiko hydras, obtained by applying a close transform after this externalize, is far more powerful, and its corresponding ordinal is the first common fixed point of “\(\alpha\) maps to the ordinal of \(\textrm{hyper}^\alpha\)-nested Buchholz hydras.”

Form of Amiko hydras

A hydra is an ordered rooted labelled tree. It would actually be more natural to assign labels to the edges, but just so we can have an easy representation, they are given to the child instead. The root then, which has no label, is given the singleton label \(\star\). In comparison, \(\star\) is considered less than all actual hydras.

Children must be ordered descending. This is a strict requirement to ensure normality. When reducing hydras, this invariant is always maintained.

Hydras are written with a \(:\) between the label and the children. For example, \((\star:((\star:):)((\star:):))\) is a hydra where the root has \(2\) children, and both those children have label \((\star:)\) and no further children.

Converting Buchholz hydras to Amiko hydras

It’s useful to be able to show a Buchholz hydra can be converted into an equivalent Amiko hydra, since it shows that Amiko hydras are at least as strong as Buchholz hydras.

The root just becomes a root node. All its children are then recursively transformed with this procedure:

Recursively transform all its children. Let \(\alpha\) be the label of the Buchholz hydra node. Change its label to \((\star:)\). If \(\alpha < \omega\), then insert \(\alpha\) copies of \(((\star:((\star:):)):)\) just before its leftmost child. Otherwise, insert \(((\star:((\star:):)):((\star:):))\) just before its leftmost child.

As you can see, the hydras converted this way are nowhere near the largest Amiko hydras allow. All original nodes now have label \((\star:)\), and the largest node we possibly injected was \(((\star:((\star:):)):((\star:):))\).

The converted Amiko hydra will not necessarily evolve exactly the same as the Buchholz hydra, but they will correspond to the same ordinal, and if analogous fast growing functions were defined on them, they would have the same growth rate.

Comparison of Amiko hydras

Comparison operators may have a filter, which refers to the labels of the immediate children of the nodes being compared, and causes children not matching the filter to be ignored. The filter does not propagate in recursive comparisons. For example, writing \(A <>_{>C} B\) means to compare \(A\) and \(B\) as if all their immediate children with labels \(\le C\) were removed.

I’m not actually sure about the comparison rules for Amiko hydras, which would decide if a hydra’s associated fast-growing function would dominate another hydra’s. My gut feeling is that it should be the same as Buchholz hydras (and thus nested Buchholz hydras), but there’s something very wrong with that. The comparison defines the ordering, which determines the order type, and thus the ordinal that describes the strength of the system. If the comparison rules were exactly the same as nested Buchholz hydras, it would imply the order type is the same, and that they are the same strength, but clearly Amiko hydras are much stronger. While I have a lot of confidence in that statement, I am also just a little skeptical, since order type is influenced not only by the ordering, but also the subset of describable elements which are considered valid - those in the normal form.

I haven’t figured out the comparison rules yet, but assuming all hydras terminate, it would be possible to derive the comparison rules from that. As a possible starting point, weaker hydras like Buchholz hydras will have their ordering preserved when converted to Amiko hydras, also implying that these converted hydras correspond to the same ordinals.

Evolution of Amiko hydras

Let \(S(A)\) be the outer reduction function, which is what we mean by reducing a hydra that includes the root node. It is defined like so:

It is guaranteed if we are reducing \(A\) that it has children. Let \(B\) be the \(A\)’s rightmost child, and let \(C\) be \(B\)’s label.

1. If \(C = (\star:)\): Search for the rightmost leaf of \(A\), but do not enter nodes with labels \( > (\star:)\). Let \(D\) be this rightmost leaf (whose label is guaranteed to be \((\star:)\)).

1.1. If \(D\) has no children: Let \(E\) be the parent of \(D\). Remove \(D\) from \(E\). If \(E\) has a parent, append \(N\) copies of \(E\) as additional children to the parent of \(E\), for some \(N\). \(S(A)\) is the modified \(A\).

1.2. If \(D\) has any children (which are guaranteed to have label \( > (\star:)\)): Traverse up the parents from \(D\) searching for a node \(E\) satisfying \(E <_{> (\star:)} D\) (but do not enter nodes with label \(> (\star:)\)), or if no suitable \(E\) is found, take \(E\) as the last candidate’s parent (or \(A\) if it was reached) but with all children removed except for the rightmost. Let \(D’\) be \(D\) but with the label changed to \(\star\). Let \(E’\) be \(S(D’)\) but without children whose label is \((\star:)\) and with the children of \(E\) whose labels are \((\star:)\) appended as children, and with the label of \(D\). Let \(F = ((\star:):)\). Do this \(N\) times, for some \(N\): “Replace \(F\) with \(E’\) where \(D\) is replaced by \(F\).” Replace \(D\) with \(F\). \(S(A)\) is the modified \(A\).

2. If \(C > (\star:)\): Go right in the tree, looking for the rightmost leaf. If \(C\) has no children the search just ends there.

2.1. If a node \(D\) with label \((\star:)\) is encountered, proceed as in rule 1.

2.2 If we reach a leaf without ever encountering a node with label \((\star:)\): Let \(D\) be this rightmost leaf. Let \(E\) be the label of \(D\). Traverse up the parents from \(D\) searching for a node \(F\) with \(G\) as the label of \(F\) satisfying \(G < E\), which is always guaranteed to exist, because the root always satisfies this. Let \(H = S(E)\). Let \(F’\) be \(F\) but with the label changed to \(H\). Let \(I = ((\star:):)\). Do this \(N\) times, for some \(N\): “Replace \(I\) with \(F’\) where \(D\) is replaced by \(I\)” Replace \(D\) with \(I\). \(S(A)\) is the modified \(A\).

The rules are sensitive to the order of recursive evaluations if the value of \(N\) depends on which comes first, as it does in the derived fast-growing function. In the future I may need to re-order the instructions to better reflect the underlying ordinal notation, though for now this is okay.

If you want to intuitively understand what each rule does:

- 1.1 is the Kirby-Paris chop and regrow rule, which Buchholz hydras also have.

- 1.2 is an adaptation of the Buchholz hydra successor stack rule. You can see the correspondence if you un-externalize the higher labelled children back into the label somehow.

- 2.1 redirects to 1. It’s perhaps not the strongest variant of the rule that’s compatible with the other rules, but it is very safe (in that it won’t accidentally make the hydra ordinal much smaller), and produces the intended behaviour as far as I know.

- 2.2 is yet another rule adapted from the Buchholz hydra successor stack rule, so perhaps you can think of it like a tier 2 Buchholz successor stack rule. It’s also responsible for reducing the labels and expanding those nodes out. It used to be weaker, and expand more like the Veblen functions, but I thought of this variant and I’m pretty sure it still always terminates so this is what I’m publishing first.

I have had to make one major revision to the rules so far because the rules as written didn’t do what I thought they were doing. Do let me know if it’s doing something weird, because that’s probably not intentional and it was a legitimate mistake when translating the idea to hard rules.

Ordinal notation

Hydras naturally yield ordinal notations, so long as you abide by the normal form rules. In fact, if you really wanted to, you could use hydras directly to denote ordinals. A hydra \(A\) is less than a hydra \(B\) if they are not identical and \(A\) can be reached from \(B\) by some series of steps. This ordering is a well-order with order type whatever the hydra system’s ordinal is. Amiko hydras follow this too, and they do correspond to some large ordinals.

However, even if Amiko hydras themselves are already an ordinal notation, this is not quite complete. If we look at Buchholz hydras, the hydras can be converted into expressions using Buchholz’s \(\psi\), which is an ordinal collapsing function defined just using ordinals. I have not yet found or created such a system for Amiko hydras, an ordinal notation defined purely using ordinals which is able to exactly mirror the structure of Amiko hydras. It seems challenging, and perhaps that is an item best left for future research.

Flattening of Amiko hydras

For some purposes, it may be useful to flatten the hydra. If hydra labels are “internal” and children are “external”, in the process of deriving Amiko hydras from the nested hydra system, we externalized that nesting already. We can also externalize the hydra labels in Amiko hydras by moving the hydra from the label into a fake first child, except for the root (and sub-roots) which will have no label. Rules would need to be slightly reworded so rules about labels instead refer to the first child and rules about children ignore the first child, but the hydras would be functionally the same, just now in tree form without further nesting. If you wanted to flatten it further, you could use any of a number of methods which represents a tree uniquely using a list.

Fast-growing function and reference number

Summary of the fast-growing function and reference number

For completeness, and for fun, I should define a fast-growing function based on Amiko hydras. So, let’s define \(AH(k)\).

Begin with the smallest possible hydra, which is \((\star:)\). Repeat \(k\) times: \(A \mapsto (\star:(A:))\). This is now the starting hydra.

Begin with a global shared counter \(N = 1\), which will increment after every time it is called for (including additional mentions when reducing nested hydras), not on each outer evaluation of \(S\). Reduce the hydra using \(S\) until it is \((\star:)\). The final value of \(N\) is \(AH(k)\).

As examples, here are the first few values of \(AH\):

\(AH(0) = 1\)

\(AH(1) = 1\)

\(AH(2) = 3\)

It only makes sense to submit one number to the ever-growing list of large numbers humans have described, since other numbers will likely be far below it or so far above it that if you replaced \(f_0\) in the fast-growing hierarchy with \(AH\) then \(f_\alpha(N)\) for reasonable ordinal \(\alpha\) and integer \(N\) it wouldn’t even get close to the other number.

\(AH(3)\) already blows Buchholz hydras (and finitely hyper-nested Buchholz hydras) out of the water, yet it doesn’t feel huge enough to really show off the strength of the construction, so I’ll take the next number after that. Thus, I put forward \(AH(4)\) to represent the Amiko hydras.

Walked expansions of sample hydras

For \(AH(0)\), the starting hydra is just \(0 = (\star:)\), and there are no steps left to take, so \(N\) stays at \(1\) and thus \(AH(0) = 1\).

For \(AH(1)\), the starting hydra is just \(1 = (\star:((\star:):))\). Rule 1.1 applies, so that child node gets chopped, but because there is no grandparent, there is no regrowth. \(N\) never increments, so \(AH(1) = 1\).

For \(AH(2)\), the starting hydra is \((\star:((\star:((\star:):)):))\).

Rule 2 applies. \(D = C = ((\star:((\star:):)):)\). \(E = 1 = (\star:((\star:):))\). \(F\) is the root. It then asks us to take \(S(E)\). We already know from before this will be \(H = S(E) = 0 = (\star:)\) and \(N\) will not increment. \(F’ = ((\star:):D)\). \(I = ((\star:):) = (0:)\). We now invoke the counter for the first time, so we use \(N = 1\) here, and it increments afterward. \(I\) becomes \(((\star:):I) = ((\star:):((\star:):)) = (0:(0:))\). Then we replace \(D\) in the original hydra, resulting in \((\star:((\star:):((\star:):))) = (\star:(0:(0:))) = \omega\), with \(N = 2\) now. That concludes the first outer step.

After this, it is a Kirby-Paris hydra, and we will repeatedly invoke rule 1.1. At the next step, the deepest child is chopped, and then \(N = 2\) heads regrow, and after that \(N = 3\). The hydra is now \((\star:((\star:):)((\star:):)((\star:):)) = (\star:(0:)(0:)(0:)) = 3\). There will be no more regrowth after this, so at the end, \(N = 3\).

For \(AH(3)\), the starting hydra is \((\star:((\star:((\star:((\star:):)):)):))\).

Rule 2 applies. \(D = C = ((\star:((\star:((\star:):)):)):)\). \(E = (\star:((\star:((\star:):)):))\). \(F\) is the root. It then asks us to take \(S(E)\). We know since we already did this once that \(H = S(E) = (\star:((\star:):((\star:):))) = (\star:(0:(0:))) = \omega\) and \(N\) increments now to \(2\). \(F’ = (H:D)\). \(I = ((\star:):) = (0:)\). We invoke the counter again, taking \(N = 2\) this time, and incrementing it afterward. After these iterations \(I\) becomes \((H:(H:(0:))) = (\omega:(\omega:(0:)))\). Then we replace \(D\) with \(I\). The hydra after the first outer step is \((\star((\star((\star):((\star):))):((\star((\star):((\star):))):((\star):)))) = (\star:(\omega:(\omega:(0:))))\).

In case you haven’t caught on yet, this is hugely more powerful than Buchholz hydras already (and finitely hyper-nested Buchholz hydras). After another step, the Kirby-Paris regrowth rule applies, resulting in the (abbreviated form) hydra \((\star:(\omega:(\omega:)(\omega:)(\omega:)(\omega:)))\) with \(N = 4\). It may not be obvious yet we’re actually doing much better, but when it comes to fast-growing functions like this, it’s not like I can just show the whole path. There’s a long descent until the \(\omega\) labels are gone though, and still much longer to termination.

A program implementing Amiko hydras

To save myself the trouble of needing to do larger hydras by hand, and to allow you to play with Amiko hydras, I wrote a program which includes all the related functionality: amiko_hydra.py. Please keep in mind I do not yet know the comparison rules for Amiko hydras, so I used the Buchholz hydras comparison rules as a placeholder. It’s not as clean as my usual code, but please forgive me, I was very excited to share this with the world so I took some shortcuts.

Higher order hydras

This whole time I’ve been avoiding mention of “higher order hydras”. A higher order theory should quantify over and work with the objects of the lower order theory, for example, first order arithmetic quantifies over integers, and second order arithmetic can now quantify over sets of integers (and thus relations on integers and real numbers). While it may be true that we used a higher order technique to get to this hydra construction, the hydras themselves are first order trees and the evolution rules are all first order computable, which I understand are very different things, but the point is I can’t find anything second order about the hydras themselves which would allow me to refer to them as second order.

For the time being, Amiko hydras are just a hydra construction that is stronger than Buchholz hydras and introduces new techniques.

Stronger hydra constructions beyond Amiko hydras

Amiko hydras are by no means the end. I’ve already introduced externalize and close, so I acknowledge that you can boost further with more iterations of externalize and close. The reason I don’t bother just presenting those instead is because Amiko hydras are in some sense the minimal example for this technique, and stacking on more externalize and close iterations does not necessarily make it more interesting. It would make it more confusing though.

I believe the next stronger hydra worthy of study must introduce something new. Buchholz introduced labels. I introduced externalize and close as higher order transformations. What comes next may be a higher order closure over the hydra constructions reachable by externalize and close, or perhaps something more novel and creative that I have not even conceived.

Though not a hydra unless it’s perhaps a flattened hydra, I want to bring attention to the Bashicu matrix system, which is one of the contenders for being a next stronger system. I haven’t studied it in depth so I do not want to make claims, but based on my first reading, I can make a guess. Keep in mind I’ve not done the analysis to confirm this, and this is only my speculation. \(2\) row Bashicu matrices are at the same strength as Buchholz hydras with labels below \(\omega\). Each close (and optionally externalize) of the kind I performed allows to match \(1\) more row in Bashicu matrices, so I believe Amiko hydras are on par with \(4\) row Bashicu matrices. We would need \(\omega\) iterations of close and externalize to match \(\omega\) row Bashicu matrices, which are the full strength of the Bashicu matrix system. That doesn’t mean there’s no hope for hydras though, since as I just said, it’s with the kind of close and externalize I used. A stronger externalize may permit a stronger close which brings us to the ordinal \(\alpha\) which is the first common fixed point of “from \(\alpha\), take the ordinal corresponding to the hydra construction created by starting with Buchholz hydras and applying the weaker kind of close and externalize \(\alpha\) times,” which surely is far beyond \(\omega\). As a vague way to conceptualize how the new rules may look, \(\alpha\) labels may correspond to the level of hydras after \(\alpha\) iterations of the weaker close and externalize. All Bashicu needs to do to match it is allow transfinite entries via embedded deeper matrices. Still, with the strength and relative simplicity of Bashicu matrices, as my personal opinion, I believe Bashicu matrices are the future for a next stronger construction, if only they can be proven to terminate.

My contributions to the field

Hydras have been used so far as independence results for a certain theory, where the corresponding hydra theorem itself and its unprovability in that theory can be proved in a slightly stronger theory. Incidentally, these hydras also defined ordinal notations up to some \(\alpha\) which is also the proof-theoretic ordinal of that weaker theory, and the fast-growing functions derived from those hydras grow similarly fast to \(f_\alpha\) in the fast-growing hierarchy. For Kirby-Paris hydras, this was Peano Arithmetic and \(\varepsilon_0\). For Buchholz hydras, this was \(\Pi_1^1-CA+BI\) and the Takeuti-Feferman-Buchholz ordinal. These ordinal notations can also be turned into actual predicative ordinal functions with normal forms - the Cantor normal form for Kirby-Paris hydras and the Buchholz’s \(\psi\) normal form for Buchholz hydras.

Hydras are useful to mathematicians. Now, I don’t have any of these other parts yet. For now, all I have is the hydras. I can perhaps answer at a later date how strong of a theory is needed to prove the termination of Amiko hydras, build a proper ordinal notation out of these hydras, and give a name to the ordinal for these hydras. Right now I’m just getting the idea out there and my name on it. I hope someday I will have the chance to study them more in depth, answer these questions, and perhaps get a paper published.

I’m open to feedback and additions, including corrections. It would be great if I nailed everything the first time, but it’s quite likely I didn’t.